Arms Without Restraint: The Destabilising Impact of China’s Military Exports

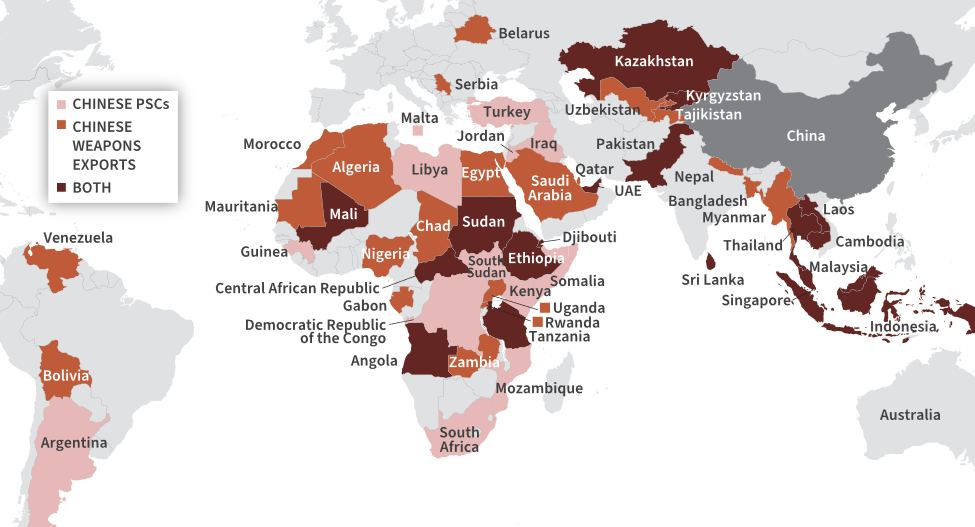

China is now one of the world’s biggest suppliers of weapons and military technology. That is a fact, not a slogan. The harder question is what this means for countries living next to old border disputes, fragile politics, and weak crisis-control systems. The answer, seen again and again, is uncomfortable: advanced weapons do not start these quarrels, but they can make them burn hotter, spread faster, and hurt more civilians.

The most recent example is the Thailand–Cambodia border fighting. The dispute itself is not new. What changed is the kind of firepower sitting in the background. During the December 2025 escalation, Thai officials said they were worried Cambodia’s Chinese-made long-range rockets could reach targets well beyond the frontier. The concern was not only about soldiers on a ridgeline. It was about what those rockets might do to infrastructure that keeps daily life running—airports, hospitals, transport nodes. Cambodia denied it would target civilians. But in war, fear often drives action faster than facts do.

That is the first problem with long-range systems. They widen the map. A border clash becomes a national security crisis because the “rear” is no longer safe. When leaders believe a first volley could hit deep inside their territory, they feel pressure to move first—strike suspected launch sites, hit supply routes, or use airpower early. Even if neither side wants a bigger war, the new range makes both sides act like they might get one.

This is not just about rockets. It is about how modern weapons change behaviour. When you add precision, sensors, and drones, you also add speed. You shorten the time available to verify claims, calm tempers, or bring commanders back under political control. In a fast-moving crisis, a rumour becomes “intelligence”, an assumption becomes “imminent threat”, and escalation becomes “self-defence”. Civilian risk rises because militaries start thinking in terms of pre-emption and denial, not containment.

Cambodia’s ties with China did not begin with this latest flare-up. Over the years, Cambodia’s armed forces have taken in Chinese equipment and training as part of broader modernisation. For a smaller country, Chinese systems are often attractive: they are affordable, available quickly, and usually come with fewer political strings. That is the sales pitch. The strategic cost is that these deals can land in regions where disputes are unresolved and tempers are never far from the surface. New weapons then do what they often do in such places: they add confidence, raise suspicion, and make a bad day at the border far more dangerous.

There is also the problem of what these exports do to accountability. When a country buys from a supplier that does not demand strong public reporting or tight end-use controls, outsiders struggle to see what is being acquired, how it is stored, and what is actually deployed. In a crisis, this lack of clarity feeds worst-case planning. If your neighbour’s arsenal is opaque, you plan for the most damaging version of it. That mindset is poison for stability.

The adverse effects become even clearer when Chinese systems show up in conflicts with weak institutions and brutal ground realities. In Sudan’s civil war, Chinese-made drones have been linked to expanded strike capability. The basic point matters: drones and guided munitions allow armed actors—sometimes not even states—to hit further, more often, and with less warning. That does not automatically mean “precision” equals “fewer civilians dead”. In many wars, it can mean the opposite. When violence becomes easier to deliver at distance, it becomes easier to repeat. A strike can be ordered from far away, with limited risk to the side launching it, and limited pause for reflection.

Then there is the supply-chain issue. Modern weapons do not always move in straight lines from factory to battlefield. They can pass through partners, brokers, and third countries. Each step adds deniability and reduces the chance of consequences. For the people living under the drones, the paperwork does not matter. What matters is that the sky is no longer empty, and that armed groups now have tools that look and feel like an air force.

China’s role also extends beyond selling finished weapons. Technical assistance, joint development, and components can have effects similar to direct transfers. The point is not to claim that every Chinese engineer abroad is building weapons. The point is that once battlefield lessons are absorbed into industrial production, the next generation of systems tends to become cheaper, more capable, and more widely available. That is how technologies spread. It is also how wars evolve.

China Supplying Arms to Pakistan

Nowhere is China’s impact on regional military balances more obvious than in Pakistan. Over the past decade, Pakistan has taken in major Chinese systems across air, sea, and missile forces. The list is not minor. It includes fighter aircraft, frigates, and other advanced platforms that shape how Pakistan plans for war and how India must plan in response.

This deep supply relationship brings clear adverse effects. It increases the pace of the arms cycle in South Asia. Every major induction on one side creates pressure on the other side to respond—through new purchases, new deployments, or new doctrines. That is not stability. That is an arms treadmill.

It also increases uncertainty. When platforms, sensors, and munitions are upgraded quietly over time, rivals struggle to judge real capability and real intent. In a crisis, uncertainty is dangerous. It pushes commanders to assume the worst and act early. In a region where escalation risks are already high, that is exactly the wrong direction.

The final cost is political. Heavy dependence on a single supplier reduces strategic flexibility. It ties training, maintenance, and spares to the relationship. It creates incentives to keep the partnership strong even when the wider region becomes more tense. That can harden blocs and reduce space for diplomatic compromise.

China’s arms exports are often discussed as if they are just business. In reality, weapons are never “just business”. They are power. They are signal. They are leverage. When advanced systems flow into disputed borders and unstable regions, they do not sit quietly in warehouses. They change how people think about risk and opportunity.

The lesson from recent conflicts is simple. The more reach a weapon has, the more fear it creates—and fear is one of the fastest paths to escalation. If the goal is regional stability, then the debate cannot stop at who sold what to whom. It must ask what those weapons do to the next crisis, the next border clash, the next night when someone panics and decides to strike first.